|

|

|

It has been six months since we moved into our new home. In that time, my husband has pointed out to me on three occasions a decluttering version of "I told you so". After discovering a use for something I chose to get rid of, he has essentially said, "This is why you don't get rid of things you might use." I adore my husband, but I respectfully disagree. In all three cases, I am content with my choice even though it meant replacing each of the items in question. Lest you think I'm a lunatic, I will endeavor to explain.

Ten years ago our youngest son did an experiment in bouyancy for his fifth grade science project. It required approximately 40 ping pong balls which we have retained in our possession ever since (until our recent move). We do not own a ping pong table or have access to one. At one point several years ago I made a vain attempt to repurpose the ping pong balls after seeing an idea on Pinterest. This involved writing tasks/activities on each ball. My son was not nearly as impressed with the idea as I was, and the ping pong balls soon found their way back to the garage. Thus, I felt completely justified in tossing them out when it came time to move. As luck would have it, mere weeks after discarding the ping pong balls, my husband was put in charge of securing supplies for a church youth activity. They planned to play a series of Minute to Win It games, one of which required...ping pong balls. Here's why I do not regret my decision to toss out those ping pong balls:

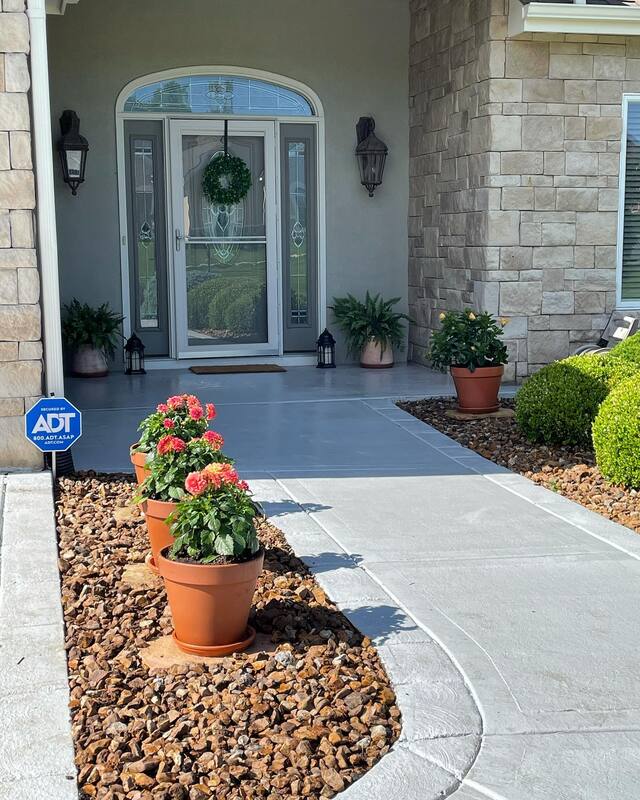

A couple of years ago we created a cement patio in our back yard. In preparation for the project, we pulled up eight square red brick pavers which have been sitting in our shop ever since. In preparation for the move, I offered them up on Facebook, and they were quickly claimed by a friend. She had the perfect spot for them. They actually solved a problem she'd been battling in her yard, and she was thrilled to get them. Several of the flower beds in our new house are filled with rock. One such bed is a narrow strip between the driveway and the front walk. A couple of weeks ago we decided to space flower pots in the rock to add some color and interest to the area. We decided it would be useful to put down pavers underneath the pots so they would sit flat. Again, my husband pointed out that we were buying something we had only recently given away, but I was completely comfortable defending that decision. Here's why:

We moved in December, and I honestly wasn't thinking much about spring and planting flowers. I was thinking about downsizing. In my zeal to lighten our load, I gave away six or eight mismatched plastic flower pots in varying sizes. All of them were sun faded and some of them were a little cracked around the rim. Now it's May, and I'm busily striving to beautify my new yard and increase my home's curb appeal (see the above entry for details). As we drove to Home Depot to shop for flower pots, my husband jokingly said, "It's too bad we didn't have a bunch of flower pots lying around that we could have used." Haha. I know. I know. Once again, I was unphased by the fact that we were replacing something we had recently owned and given away, and this is why:

Might is a word I hear often as an organizer. "I can't get rid of that because it might come in handy." Or "You never know when you might need a...." Other related words include ought, should, and could. All of these words convey a sense of uncertainty coupled with a vague notion of obligation. Most people, if questioned, would no doubt indicate an unwillingness to let fear serve as a primary motivator for their decisions and behavior. Yet many of us do just that when we succumb to the influence of 'might'. In essence, we let our belongings bully us. We keep things that serve no apparent or meaningful purpose in our lives - things we have no emotional attachment to or conceivable use for - simply because they might be needed. Instead of sacrificing precious space for things that may or may not prove useful at some future date, why not make space for the things you have a use for and interest in right now?

A client recently complained to me that "organizers always say that holding onto things you might need is pointless because you never use them." I admit, I'm guilty as charged. This person went on to express her amazement at how many times she has been saved at the last minute because she held onto something she needed. This well-meaning individual failed to see the flaw in her reasoning, which is this: there is a difference between an actual need/use and a hypothetical one. In her case, she was actually using the things she had chosen to keep. The problem arises when we aren't sure when or if an item will prove useful. If you can visualize a legitimate use for something, by all means, hold onto that item. If, however, you only have an ambiguous notion that it could serve some purpose someday - but no real notion of what that purpose could be - please consider getting rid of the item.

When trying to determine which of your 'mights' are legitimate and which are simply nebulous, I recommend doing a cost comparison. There are many different costs associated with keeping vs. replacing an item. Consider the following:

When it comes down to it, there are a couple of questions we should ask ourselves when considering whether or not to keep the 'mights' in our lives:

There is no wrong answer to these questions. Only you can decide what a particular thing is worth to you, but I encourage you to take the time to think it through. If you decide you value other intangibles over the item, you can feel confident letting it go, even if a use actually does arise in the future. I hope that I have demonstrated through my personal experiences that discovering you could have used something you got rid of doesn't have to be devastating. In fact, it can be validating. In each of the cases I shared, I discovered that what I had wasn't really what I wanted. While the items in question could have been used to satisfy my purposes, I would not have been as happy with the results.

10 Comments

My husband writes books, and I edit them. Editing can be a tedious task. It takes time and concentration to make a careful, deliberate review of the material. When I edit my husband's writing, I am looking for typos and grammatical errors (copy editing), but I am also evaluating the effectiveness of his argument and the fluidity of the text (content editing). I'm not just interested in whether his work is written properly; I'm interested in whether it is written well. I want it to be a true and compelling representation of his thoughts and ideas. It occurred to me recently that decluttering and downsizing are kind of like editing. In fact, the word edit can mean to expunge or eliminate [the unnecessary]. While this definition is highly appropriate to a discussion about removing clutter, I also like applying the more common (grammatical) definition of edit, which is to revise or correct. When we downsize and declutter, our goal shouldn't be limited to removing the excess, but also to setting things right in our environment (i.e. revising and correcting). To me, the ideal space is one that is a true reflection of its owner. Clutter has a way of crowding in and making itself at home, obsuring the purpose and personality of a space in the process. Editing a space allows us to revise its form and function so that it becomes a proper depiction of who we are, what we value, the road we've traveled, and how we like to live. When editing your own or someone else's writing, there are certain things you look for and eliminate in order to make the work the best it can be. The same is true for editing your space.

Mistakes in spelling, sentence structure, subject-verb agreement, and other common grammatical errors are the most obvious to search for and often the easiest to spot when editing a piece of writing. The same is true for mistakes in stuff. In this category I would include anything you purchased, or received as a gift or hand-me-down, which you do not like, need, or use. They are the things people hang onto out of a sense of guilt or obligation, and they could be almost anything. Examples include:

We all make mistakes in stuff on a regular basis. These mistakes help us to refine our tastes. In this way, they are not a waste, and we can feel good about letting them go and moving on with our lives.

To be inconsistent is to lack harmony or agreement, to be at variance. In wiriting, inconsistencies are those sentences or ideas that don't seem to have a place in the overall work. They may be related, but not closely enough to blend well with the rest of the text. They leave the reader wondering, "What's that got to do with anything?" Inconsistencies in our personal possessions are similar in that they do not seem to belong. They seem incongruent. They may be items we have purchased ourselves, or they may be things that we were gifted in one form or another. If you've ever looked at a thing and thought, "This really isn't me," you've encountered an inconsistency in your possessions. Chances are, if you don't like a thing it's because it doesn't speak to you; it's not in harmony with your interests or tastes or conceptions. If that is the case, you can feel comfortable parting with whatever it may be, even if it was given to you by someone else. You need feel no obligation to keep things other people think you might (or even should) like or use. Only keep those things that represent a true reflection of you.

It can be tempting as a writer to restate a concept in a slightly different way for added emphasis, but this practice can grate on readers if it seems as though the author is just repeating himself. While we may not enjoy redundancy as readers, many of us practice it openly with regard to our possessions. Redundancy occurs anytime we have multiples of an item when one or two would do nicely. It is good to have multiples of some things. Obvious examples are bath towels, underwear, dinner plates, and cutlery, to name just a few. In many cases, though, redundancy (or multiples) only increase the clutter in a home without being truly useful. A good way to determine whether or not a particular item is a good candidate for maintaining multiples is to ask yourself:

If your answer is no, you don't use them all because, yes, you do have a favorite, you can feel comfortable getting rid of the extras. They are not serving a purpose; they are just taking up space.

In addition to writing books, my husband teaches history. While grading papers recently, he came across a student whose work was rife with unreasonably lengthy sentences - 100 words or more. For a reader, such lengthy statements are difficult to digest. One gets lost in the middle and forgets what the point of the sentence was or how it ties to other ideas being expressed. The same can be true of possessions, particularly collections. Too much of a good thing is not a good thing. It's tempting when you begin collecting to snatch up any item you encounter that fits your collection. In addition, friends and family often add to collections at gift-giving occasions because it's easy to buy for someone if you know they love ceramic chickens or sports memorabilia or all things Star Wars. As with multiples in other forms (as mentioned in the previous section), some specimens are better than others, and the collector will undoubtedly have favorites. Editing a collection can actually add to its charm and visual impact. A few good pieces will stand out and draw people's attention like a true focal point. On the other hand, a dizzying array of related pieces often reads as clutter to the mind. Nothing stands out and demands to be noticed because everything gets lost in the jumble.

As a military historian, my husband has written on a number of topics (such as the Iraq War, the rise of ISIS, and the War in Afghanistan) which are ongoing in nature. Because these topics are continually evolving, part of the editing process involves making sure that the information included in the book is the most up-t0-date information available at the time of publication. When it comes to our homes, we often don't have to look far to find items which are either outdated or incomplete. Outdated items could include electronics, clothing, media, books, reference materials, software, or calendars and planners, to name a few. They may have gone out of style, been surpassed by newer technology, or contain information that is no longer accurate. As for incomplete items, this would include anything that is missing parts or pieces. For some inexplicable reason, we (including me!) have a tendency to hold onto such things, even though they no longer work properly. Be they puzzles or appliances, they do not deserve a place in your space if they do not work as intended. Both of these types of items are simple to edit as they often have no sentimental or inherent value. Chances are you know exactly where they are located, so finding them and getting rid of them should be easy work. As an editor and an organizer, I hope you will apply these suggestions for editing your space. Doing so serves much the same purpose as editing a written product; it makes the space better, more enjoyable to experience, easier to work with (or within), and nicer to share with others.

People often talk about leading a more "balanced life". It is my belief that this phrase arose from the notion that you can "do (or have) it all". It's a way of expressing a desire to achieve a sense of stability and calmness amid the chaos of a busy life. The problem is a balanced life is not possible, nor is it truly desireable. There are a number of reasons why this is the case.

Balance, by its very nature, is fleeting. Try standing on one foot. Yes, you can do it. But for how long? With practice, you may be able to improve your performance, but you will need to rest and readjust regularly in order to prevent yourself from toppling over. In addition, priorities, needs, and circumstances are constantly shifting making it necessary to adapt and change. The idea that there is some magic formula we can apply to achieve the permanent end goal of a balanced life is a fantasy. The moment you feel as though equilibrium is within reach, something will change. A new need will arise, upsetting your stability and forcing you to adapt. Balance also implies equality of importance. In order for something to be balanced, the different elements have to be equally weighted. When it comes to life, responsibilities, and time management, equality is not the goal. Some things simply require more of our time, energy, focus, and commitment than others, and that's a good thing. Imagine what life would be like if every aspect of our lives (work, family, social interactions, home maintenance, civic duties, personal development, and more) required and received an equal degree of importance and attention. It would be overwhelming and exhausting, to say the least, and oddly enough, it would leave us feeling unbalanced. When we speak of balance, what we really mean is that we want to have enough time, energy, and resources to focus on the things that really matter and not neglect the things we value most.

We all know that there are an infinite number of hours in the day. What we sometimes forget is that we can only do so much in the hours that we have. Author and motivational speaker Jon Acuff stated it well when he said:

In other words, it is necessary to prioritize. If a particular thing is important, then other things must, by necessity, receive less attention. For this reason, I think of life, not as a balancing act, but as a juggling act. Juggling implies a more fluid, changing environment. Think of all the aspects of your life as balls. You can only hold one or two balls at a time, thus requiring you to juggle. If you try to juggle too many things at once, you will drop some of your balls. At any given moment, some balls are more important than others. They are made of glass; other balls are made of rubber. You cannot drop a glass ball, or it will break. Rubber balls, on the other hand, are safe to drop because they will bounce and remain intact until you are able to retrieve them. The secret is to determine which balls are glass and which are rubber, knowing that the nature of the ball will change depending on your circumstances and season of life and personal priorities. Some balls even change in nature during the course of a single day. For example, when you are at work, work requires your focus. It is a glass ball. But when you are at home, other things become more important. The key to success is to learn to discern which balls you can afford to drop or set down and which ones you have to keep in the air at any given time. When we choose in advance what to focus on and what to ignore, we free ourselves from guilt and shame. Instead of feeling bad about some ball you’ve dropped, you can feel empowered by your own mindfulness in deciding not to pick that ball up to for the time being.

Once you buy into the idea that life is not a balancing act, there is much to learn from the juggling analogy. Consider the following:

If you're tired of trying to achieve the impossible ideal of a balanced life, I encourage you to take a step back and reevaluate your situation. Instead of trying to do it all, make an accessment of what matters most. Give yourself permission to set down some of your balls from time to time. Decide when you can best give time and energy to the things that truly matter in your life. Be mindful in the moment by switching balls out periodically to reflect your priorities. Enjoy focusing your energy, effort, and heart on a few essentials and let the extraneaous balls bounce off into the corner until (and if) you are ready to retrieve them.

|

Archives

November 2022

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed